This HTML version of Think Java is provided for convenience, but it is not the best format of the book. In particular, some of the symbols are not rendered correctly.

You might prefer to read the PDF version, or you can buy a hardcopy at Amazon.

Chapter 13 Objects of arrays

In the previous chapter, we defined a class to represent cards and used an array of Card objects to represent a deck.

In this chapter, we take another step toward object-oriented programming by defining a class to represent a deck of cards. And we present algorithms for shuffling and sorting arrays.

The code for this chapter is in Card.java and Deck.java, which are in the directory ch13 in the repository for this book. Instructions for downloading this code are on page ??.

13.1 The Deck class

The main idea of this chapter is to create a Deck class that encapsulates an array of Cards.

The initial class definition looks like this:

| public class Deck { private Card[] cards; public Deck(int n) { this.cards = new Card[n]; } } |

The constructor initializes the instance variable with an array of n cards, but it doesn’t create any card objects.

Figure 13.1 shows what a Deck looks like with no cards.

We’ll add a second constructor that makes a standard 52-card deck and populates it with Card objects:

| public Deck() { this.cards = new Card[52]; int index = 0; for (int suit = 0; suit <= 3; suit++) { for (int rank = 1; rank <= 13; rank++) { this.cards[index] = new Card(rank, suit); index++; } } } |

This method is similar to the example in Section 12.6; we just turned it into a constructor.

We can now create a standard Deck like this:

| Deck deck = new Deck(); |

Now that we have a Deck class, we have a logical place to put methods that pertain to decks.

Looking at the methods we have written so far, one obvious candidate is printDeck from Section 12.6.

| public void print() { for (int i = 0; i < this.cards.length; i++) { System.out.println(this.cards[i]); } } |

When you transform a static method into an instance method, it usually gets shorter.

We can simply type deck.print() to invoke the instance method.

13.2 Shuffling decks

For most card games you need to be able to shuffle the deck; that is, put the cards in a random order. In Section 8.7 we saw how to generate random numbers, but it is not obvious how to use them to shuffle a deck.

One possibility is to model the way humans shuffle, which is usually dividing the deck in two halves and then choosing alternately from each one. Since humans usually don’t shuffle perfectly, after about seven iterations the order of the deck is pretty well randomized.

But a computer program would have the annoying property of doing a perfect shuffle every time, which is not very random. In fact, after eight perfect shuffles, you would find the deck back in the order you started in! (For more information, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Faro_shuffle.)

A better shuffling algorithm is to traverse the deck one card at a time, and at each iteration choose two cards and swap them. Here is an outline of how this algorithm works. To sketch the program, we will use a combination of Java statements and English. This technique is sometimes called pseudocode.

| for each index i { // choose a random number between i and length - 1 // swap the ith card and the randomly-chosen card } |

The nice thing about pseudocode is that it often makes clear what methods you are going to need.

In this case, we need a method that chooses a random integer between low and high, and a method that takes two indexes and swaps the cards at those positions.

Methods like these are called helper methods, because they help you implement more complex algorithms.

And this process – writing pseudocode first and then writing methods to make it work – is called top-down development (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Top-down_and_bottom-up_design).

One of the exercises at the end of the chapter asks you to write the helper methods randomInt and swapCards and use them to implement shuffle.

13.3 Selection sort

Now that we have messed up the deck, we need a way to put it back in order. There is an algorithm for sorting that is ironically similar to the algorithm for shuffling. It’s called selection sort, because it works by traversing the array repeatedly and selecting the lowest (or highest) remaining card each time.

During the first iteration, we find the lowest card and swap it with the card in the 0th position. During the ith iteration, we find the lowest card to the right of i and swap it with the ith card. Here is pseudocode for selection sort:

| public void selectionSort() { for each index i { // find the lowest card at or to the right of i // swap the ith card and the lowest card found } } |

Again, the pseudocode helps with the design of the helper methods.

In this algorithm we can use swapCards again, so we only need a method to find the lowest card; we’ll call it indexLowest.

One of the exercises at the end of the chapter asks you to write the helper method indexLowest and use it to implement selectionSort.

13.4 Merge sort

Selection sort is a simple algorithm, but it is not very efficient. To sort n items, it has to traverse the array n−1 times. Each traversal takes an amount of time proportional to n. The total time, therefore, is proportional to n2.

In the next two sections, we’ll develop a more efficient algorithm called merge sort. To sort n items, merge sort takes time proportional to n log2 n. That may not seem impressive, but as n gets big, the difference between n2 and n log2 n can be enormous.

For example, log2 of one million is around 20. So if you had to sort a million numbers, selection sort would require one trillion steps; merge sort would require only 20 million.

The idea behind merge sort is this: if you have two subdecks, each of which has already been sorted, it is easy and fast to merge them into a single, sorted deck. Try this out with a deck of cards:

- Form two subdecks with about 10 cards each, and sort them so that when they are face up the lowest cards are on top. Place both decks face up in front of you.

- Compare the top card from each deck and choose the lower one. Flip it over and add it to the merged deck.

- Repeat step 2 until one of the decks is empty. Then take the remaining cards and add them to the merged deck.

The result should be a single sorted deck. In the next few sections, we’ll explain how to implement this algorithm in Java.

13.5 Subdecks

The first step of merge sort is to split the deck into two subdecks, each with about half the cards.

So we might want a method, subdeck, that takes a deck and a range of indexes.

It returns a new deck that contains the specified subset of the cards:

| public Deck subdeck(int low, int high) { Deck sub = new Deck(high - low + 1); for (int i = 0; i < sub.cards.length; i++) { sub.cards[i] = this.cards[low + i]; } return sub; } |

The first line creates an unpopulated subdeck.

Inside the for loop, the subdeck gets populated with copies of references from the deck.

The length of the subdeck is high - low + 1, because both the low card and the high card are included.

This sort of computation can be confusing, and forgetting the + 1 often leads to “off-by-one” errors.

Drawing a picture is usually the best way to avoid them.

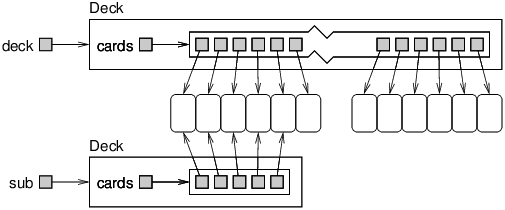

Figure 13.2 is a state diagram of a subdeck with low = 0 and high = 4.

The result is a hand with five cards that are shared with the original deck; that is, they are aliased.

Aliasing might not be a good idea, because changes to shared cards would be reflected in multiple decks.

But since Card objects are immutable, this kind of aliasing is not a problem at all.

13.6 Merging decks

The next helper method we need is merge, which takes two sorted subdecks and returns a new deck containing all cards from both decks, in order.

Here’s what the algorithm looks like in pseudocode, assuming the subdecks are named d1 and d2:

| public static Deck merge(Deck d1, Deck d2) { // create a new deck big enough for all the cards // use the index i to keep track of where we are at in // the first deck, and the index j for the second deck int i = 0; int j = 0; |

| // the index k traverses the result deck for (int k = 0; k < result.cards.length; k++) { // if d1 is empty, d2 wins // if d2 is empty, d1 wins // otherwise, compare the two cards // add the winner to the new deck at position k // increment either i or j } // return the new deck } |

One of the exercises at the end of the chapter asks you to implement merge.

13.7 Adding recursion

Once your merge method is working correctly, you can try out a simple version of merge sort:

| public Deck almostMergeSort() { // divide the deck into two subdecks // sort the subdecks using selectionSort // merge the two halves and return the result } |

An exercise at the end of the chapter asks you to implement this algorithm. Once you get it working, the real fun begins! The magical thing about merge sort is that it is inherently recursive.

At the point where you sort the subdecks, why should you invoke the slower algorithm, selectionSort?

Why not invoke the spiffy new mergeSort you are in the process of writing?

Not only is that a good idea, it is necessary to achieve the log2 performance advantage.

To make mergeSort work recursively, you have to add a base case; otherwise it repeats forever.

A simple base case is a subdeck with 0 or 1 cards.

If mergeSort receives such a small subdeck, it can return it unmodified since it would already be sorted.

The recursive version of mergeSort should look something like this:

| public Deck mergeSort() { // if the deck is 0 or 1 cards, return it // divide the deck into two subdecks // sort the subdecks using mergeSort // merge the two halves and return the result } |

As usual, there are two ways to think about recursive programs: you can think through the entire flow of execution, or you can make the “leap of faith” (see Section 6.8). This example should encourage you to make the leap of faith.

When you used selectionSort to sort the subdecks, you didn’t feel compelled to follow the flow of execution.

You just assumed it works because you had already debugged it.

And all you did to make mergeSort recursive was replace one sorting algorithm with another.

There is no reason to read the program any differently.

Well, almost. You might have to give some thought to getting the base case right and making sure that you reach it eventually. But other than that, writing the recursive version should be no problem.

13.8 Vocabulary

- pseudocode:

- A way of designing programs by writing rough drafts in a combination of English and Java.

- helper method:

- Often a small method that does not do anything enormously useful by itself, but which helps another, more complex method.

- top-down development:

- Breaking down a problem into sub-problems, and solving each sub-problem one at a time.

- selection sort:

- A simple sorting algorithm that searches for the smallest or largest element n times.

- merge sort:

- A recursive sorting algorithm that divides an array into two parts, sorts each part (using merge sort), and merges the results.

13.9 Exercises

The code for this chapter is in the ch13 directory of ThinkJavaCode. See page ?? for instructions on how to download the repository. Before you start the exercises, we recommend that you compile and run the examples.

- In the repository for this book, you should find a file called Deck.java that contains the code in this chapter. Check that you can compile it in your environment.

- Add a

Deckmethod calledrandomIntthat takes two integers,lowandhigh, and returns a random integer betweenlowandhigh, including both. You can use thenextIntprovided byjava.util.Random, which we saw in Section 8.7. But you should avoid creating aRandomobject every timerandomIntis invoked. - Write a method called

swapCardsthat takes two indexes and swaps the cards at the given locations. - Write a method called

shufflethat uses the algorithm in Section 13.2.

- Write a method called

indexLowestthat uses thecompareCardmethod to find the lowest card in a given range of the deck (fromlowIndextohighIndex, including both). - Write a method called

selectionSortthat implements the selection sort algorithm in Section 13.3. - Using the pseudocode in Section 13.4, write the method called

merge. The best way to test it is to build and shuffle a deck. Then usesubdeckto form two small subdecks, and use selection sort to sort them. Then you can pass the two halves tomergeto see if it works. - Write the simple version of

mergeSort, the one that divides the deck in half, usesselectionSortto sort the two halves, and usesmergeto create a new, sorted deck. - Write a recursive version of

mergeSort. Remember thatselectionSortis a modifier andmergeSortis a pure method, which means that they get invoked differently:deck.selectionSort(); // modifies an existing deck deck = deck.mergeSort(); // replaces old deck with new

insertionSort that implements this algorithm.

toString method for the Deck class.

It should return a single string that represents the cards in the deck.

When it’s printed, this string should display the same results as the print method in Section 13.1.Hint: You can use the + operator to concatenate strings, but it is not very efficient.

Consider using java.lang.StringBuilder; you can find the documentation by doing a web search for “Java StringBuilder”.

Are you using one of our books in a class?

We'd like to know about it. Please consider filling out this short survey.