Chapter 9 Mutable objects

Strings are objects, but they are atypical objects because

- They are immutable.

- They have no attributes.

- You don’t have to use new to create one.

In this chapter, we use two objects from Java libraries, Point and Rectangle. But first, I want to make it clear that these points and rectangles are not graphical objects that appear on the screen. They are values that contain data, just like ints and doubles. Like other values, they are used internally to perform computations.

9.1 Packages

The Java libraries are divided into packages, including java.lang, which contains most of the classes we have used so far, and java.awt, the Abstract Window Toolkit (AWT), which contains classes for windows, buttons, graphics, etc.

To use a class defined in another package, you have to import it. Point and Rectangle are in the java.awt package, so to import them like this:

All import statements appear at the beginning of the program, outside the class definition.

The classes in java.lang, like Math and String, are imported automatically, which is why we haven’t needed the import statement yet.

9.2 Point objects

A point is two numbers (coordinates) that we treat collectively as a single object. In mathematical notation, points are often written in parentheses, with a comma separating the coordinates. For example, (0, 0) indicates the origin, and (x, y) indicates the point x units to the right and y units up from the origin.

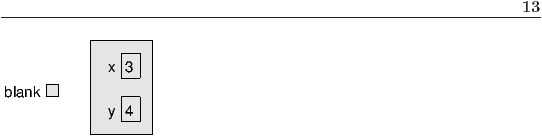

In Java, a point is represented by a Point object. To create a new point, you have to use new:

The first line is a conventional variable declaration: blank has type Point. The second line invokes new, specifies the type of the new object, and provides arguments. The arguments are the coordinates of the new point, (3, 4).

The result of new is a reference to the new point, so blank contains a reference to the newly-created object. There is a standard way to diagram this assignment, shown in the figure.

As usual, the name of the variable blank appears outside the box and its value appears inside the box. In this case, that value is a reference, which is shown graphically with an arrow. The arrow points to the object we’re referring to.

The big box shows the newly-created object with the two values in it. The names x and y are the names of the instance variables.

Taken together, all the variables, values, and objects in a program are called the state. Diagrams like this that show the state of the program are called state diagrams. As the program runs, the state changes, so you should think of a state diagram as a snapshot of a particular point in the execution.

9.3 Instance variables

The pieces of data that make up an object are called instance variables because each object, which is an instance of its type, has its own copy of the instance variables.

It’s like the glove compartment of a car. Each car is an instance of the type “car,” and each car has its own glove compartment. If you ask me to get something from the glove compartment of your car, you have to tell me which car is yours.

Similarly, if you want to read a value from an instance variable, you have to specify the object you want to get it from. In Java this is done using “dot notation.”

The expression blank.x means “go to the object blank refers to, and get the value of x.” In this case we assign that value to a local variable named x. There is no conflict between the local variable named x and the instance variable named x. The purpose of dot notation is to identify which variable you are referring to unambiguously.

You can use dot notation as part of any Java expression, so the following are legal.

The first line prints 3, 4; the second line calculates the value 25.

9.4 Objects as parameters

You can pass objects as parameters in the usual way. For example:

This method takes a point as an argument and prints it in the standard format. If you invoke printPoint(blank), it prints (3, 4). Actually, Java already has a method for printing Points. If you invoke System.out.println(blank), you get

This is a standard format Java uses for printing objects. It prints the name of the type, followed by the names and values of the instance variables.

As a second example, we can rewrite the distance method from Section 6.2 so that it takes two Points as parameters instead of four doubles.

The typecasts are not really necessary; I added them as a reminder that the instance variables in a Point are integers.

9.5 Rectangles

Rectangles are similar to points, except that they have four instance variables: x, y, width and height. Other than that, everything is pretty much the same.

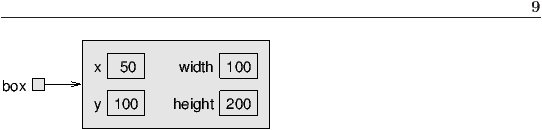

This example creates a Rectangle object and makes box refer to it.

This figure shows the effect of this assignment.

If you print box, you get

Again, this is the result of a Java method that knows how to print Rectangle objects.

9.6 Objects as return types

You can write methods that return objects. For example, findCenter takes a Rectangle as an argument and returns a Point that contains the coordinates of the center of the Rectangle:

Notice that you can use new to create a new object, and then immediately use the result as the return value.

9.7 Objects are mutable

You can change the contents of an object by making an assignment to one of its instance variables. For example, to “move” a rectangle without changing its size, you can modify the x and y values:

The result is shown in the figure:

We can encapsulate this code in a method and generalize it to move the rectangle by any amount:

The variables dx and dy indicate how far to move the rectangle in each direction. Invoking this method has the effect of modifying the Rectangle that is passed as an argument.

prints java.awt.Rectangle[x=50,y=100,width=100,height=200].

Modifying objects by passing them as arguments to methods can be useful, but it can also make debugging more difficult because it is not always clear which method invocations do or do not modify their arguments. Later, I discuss some pros and cons of this programming style.

Java provides methods that operate on Points and Rectangles. You can read the documentation at http://download.oracle.com/javase/6/docs/api/java/awt/Point.html and http://download.oracle.com/javase/6/docs/api/java/awt/Rectangle.html.

For example, translate has the same effect as moveRect, but instead of passing the Rectangle as an argument, you use dot notation:

9.8 Aliasing

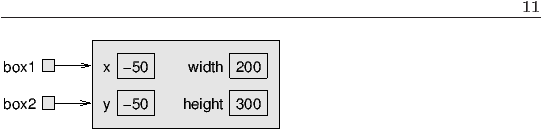

Remember that when you assign an object to a variable, you are assigning a reference to an object. It is possible to have multiple variables that refer to the same object. For example, this code:

generates a state diagram that looks like this:

box1 and box2 refer to the same object. In other words, this object has two names, box1 and box2. When a person uses two names, it’s called aliasing. Same thing with objects.

When two variables are aliased, any changes that affect one variable also affect the other. For example:

The first line prints 100, which is the width of the Rectangle referred to by box2. The second line invokes the grow method on box1, which expands the Rectangle by 50 pixels in every direction (see the documentation for more details). The effect is shown in the figure:

Whatever changes are made to box1 also apply to box2. Thus, the value printed by the third line is 200, the width of the expanded rectangle. (As an aside, it is perfectly legal for the coordinates of a Rectangle to be negative.)

As you can tell even from this simple example, code that involves aliasing can get confusing fast, and can be difficult to debug. In general, aliasing should be avoided or used with care.

9.9 null

When you create an object variable, remember that you are creating a reference to an object. Until you make the variable point to an object, the value of the variable is null. null is a special value (and a Java keyword) that means “no object.”

The declaration Point blank; is equivalent to this initialization

and is shown in the following state diagram:

The value null is represented by a small square with no arrow.

If you try to use a null object, either by accessing an instance variable or invoking a method, Java throws a NullPointerException, prints an error message and terminates the program.

On the other hand, it is legal to pass a null object as an argument or receive one as a return value. In fact, it is common to do so, for example to represent an empty set or indicate an error condition.

9.10 Garbage collection

In Section 9.8 we talked about what happens when more than one variable refers to the same object. What happens when no variable refers to an object? For example:

The first line creates a new Point object and makes blank refer to it. The second line changes blank so that instead of referring to the object, it refers to nothing (the null object).

If no one refers to an object, then no one can read or write any of its values, or invoke a method on it. In effect, it ceases to exist. We could keep the object in memory, but it would only waste space, so periodically as your program runs, the system looks for stranded objects and reclaims them, in a process called garbage collection. Later, the memory space occupied by the object will be available to be used as part of a new object.

You don’t have to do anything to make garbage collection happen, and in general you will not be aware of it. But you should know that it periodically runs in the background.

9.11 Objects and primitives

There are two kinds of types in Java, primitive types and object types. Primitives, like int and boolean begin with lower-case letters; object types begin with upper-case letters. This distinction is useful because it reminds us of some of the differences between them:

- When you declare a primitive variable, you get storage space for a primitive value. When you declare an object variable, you get a space for a reference to an object. To get space for the object itself, you have to use new.

- If you don’t initialize a primitive type, it is given a default value that depends on the type. For example, 0 for ints and false for booleans. The default value for object types is null, which indicates no object.

- Primitive variables are well isolated in the sense that there is nothing you can do in one method that will affect a variable in another method. Object variables can be tricky to work with because they are not as well isolated. If you pass a reference to an object as an argument, the method you invoke might modify the object, in which case you will see the effect. Of course, that can be a good thing, but you have to be aware of it.

There is one other difference between primitives and object types. You cannot add new primitives to Java (unless you get yourself on the standards committee), but you can create new object types! We’ll see how in the next chapter.

9.12 Glossary

- package:

- A collection of classes. Java classes are organized in packages.

- AWT:

- The Abstract Window Toolkit, one of the biggest and commonly-used Java packages.

- instance:

- An example from a category. My cat is an instance of the category “feline things.” Every object is an instance of some class.

- instance variable:

- One of the named data items that make up an object. Each object (instance) has its own copy of the instance variables for its class.

- reference:

- A value that indicates an object. In a state diagram, a reference appears as an arrow.

- aliasing:

- The condition when two or more variables refer to the same object.

- garbage collection:

- The process of finding objects that have no references and reclaiming their storage space.

- state:

- A complete description of all the variables and objects and their values, at a given point during the execution of a program.

- state diagram:

- A snapshot of the state of a program, shown graphically.

9.13 Exercises

- For the following program, draw a stack diagram showing the local variables and parameters of main and riddle, and show any objects those variables refer to.

- What is the output of this program?

The point of this exercise is to make sure you understand the mechanism for passing Objects as parameters.

- For the following program, draw a stack diagram showing the state of the program just before distance returns. Include all variables and parameters and the objects those variables refer to.

- What is the output of this program?

- What is the output of the following program?

- Draw a state diagram that shows the state of the program just before the end of main. Include all local variables and the objects they refer to.

- At the end of main, are p1 and p2 aliased? Why or why not?

- Create a new program called Big.java and write an iterative version of factorial.

- Print a table of the integers from 0 to 30 along with their factorials. At some point around 15, you will probably see that the answers are not right any more. Why not?

- BigIntegers are Java objects that can represent arbitrarily big integers. There is no upper bound except the limitations of memory size and processing speed. Read the documentation of BigIntegers at http://download.oracle.com/javase/6/docs/api/java/math/BigInteger.html.

- To use BigIntegers, you have to add import java.math.BigInteger to the beginning of your program.

- There are several ways to create a

BigInteger, but the one I recommend uses valueOf.

The following code converts an integer to a BigInteger:int x = 17; BigInteger big = BigInteger.valueOf(x);

Type in this code and try it out. Try printing a BigInteger.

- Because BigIntegers are not primitive types,

the usual math operators don’t work. Instead we

have to use methods like add. To

add two BigIntegers, invoke add on one

and pass the other as an argument. For example:BigInteger small = BigInteger.valueOf(17); BigInteger big = BigInteger.valueOf(1700000000); BigInteger total = small.add(big);

Try out some of the other methods, like multiply and pow.

- Convert factorial so that it performs its calculation using BigIntegers and returns a BigInteger as a result. You can leave the parameter alone—it will still be an integer.

- Try printing the table again with your modified factorial method. Is it correct up to 30? How high can you make it go? I calculated the factorial of all the numbers from 0 to 999, but my machine is pretty slow, so it took a while. The last number, 999!, has 2565 digits.

The problem with this method is that it only works if the result is smaller than 2 billion. Rewrite it so that the result is a BigInteger. The parameters should still be integers, though.

You can use the BigInteger methods add and multiply, but don’t use pow, which would spoil the fun.

Like this book?

Are you using one of our books in a class?

We'd like to know about it. Please consider filling out this short survey.