This HTML version of Think Java is provided for convenience, but it is not the best format of the book. In particular, some of the symbols are not rendered correctly.

You might prefer to read the PDF version, or you can buy a hardcopy at Amazon.

Chapter 11 Classes

Whenever you define a new class, you also create a new type with the same name.

So way back in Section 1.4, when we defined the class Hello, we created a type named Hello.

We didn’t declare any variables with type Hello, and we didn’t use new to create a Hello object.

It wouldn’t have done much if we had – but we could have!

In this chapter, we will define classes that represent useful object types. We will also clarify the difference between classes and objects. Here are the most important ideas:

- Defining a class creates a new object type with the same name.

- Every object belongs to some object type; that is, it is an instance of some class.

- A class definition is like a template for objects: it specifies what attributes the objects have and what methods can operate on them.

- The

newoperator instantiates objects, that is, it creates new instances of a class. - Think of a class like a blueprint for a house: you can use the same blueprint to build any number of houses.

- The methods that operate on an object type are defined in the class for that object.

11.1 The Time class

One common reason to define a new class is to encapsulate related data in an object that can be treated as a single unit. That way, we can use objects as parameters and return values, rather than passing and returning multiple values. This design principle is called data encapsulation.

We have already seen two types that encapsulate data in this way: Point and Rectangle.

Another example, which we will implement ourselves, is Time, which represents a time of day.

The data encapsulated in a Time object are an hour, a minute, and a number of seconds.

Because every Time object contains these data, we define attributes to hold them.

Attributes are also called instance variables, because each instance has its own variables (as opposed to class variables, coming up in Section 12.3).

The first step is to decide what type each variable should be.

It seems clear that hour and minute should be integers.

Just to keep things interesting, let’s make second a double.

Instance variables are declared at the beginning of the class definition, outside of any method. By itself, this code fragment is a legal class definition:

| public class Time { private int hour; private int minute; private double second; } |

The Time class is public, which means that it can be used in other classes.

But the instance variables are private, which means they can only be accessed from inside the Time class.

If you try to read or write them from another class, you will get a compiler error.

Private instance variables help keep classes isolated from each other so that changes in one class won’t require changes in other classes. It also simplifies what other programmers need to understand in order to use your classes. This kind of isolation is called information hiding.

11.2 Constructors

After declaring the instance variables, the next step is to define a constructor, which is a special method that initializes the instance variables. The syntax for constructors is similar to that of other methods, except:

- The name of the constructor is the same as the name of the class.

- Constructors have no return type (and no return value).

- The keyword

staticis omitted.

Here is an example constructor for the Time class:

| public Time() { this.hour = 0; this.minute = 0; this.second = 0.0; } |

This constructor does not take any arguments. Each line initializes an instance variable to zero (which in this example means midnight).

The name this is a keyword that refers to the object we are creating.

You can use this the same way you use the name of any other object.

For example, you can read and write the instance variables of this, and you can pass this as an argument to other methods.

But you do not declare this, and you can’t make an assignment to it.

A common error when writing constructors is to put a return statement at the end.

Like void methods, constructors do not return values.

To create a Time object, you must use the new operator:

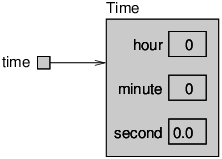

| Time time = new Time(); |

When you invoke new, Java creates the object and calls your constructor to initialize the instance variables.

When the constructor is done, new returns a reference to the new object.

In this example, the reference gets assigned to the variable time, which has type Time.

Figure 11.1 shows the result.

Beginners sometimes make the mistake of invoking new inside the constructor.

You don’t have to, and you shouldn’t.

In this example, invoking new Time() in the constructor causes an infinite recursion:

| public Time() { new Time(); // wrong! this.hour = 0; this.minute = 0; this.second = 0.0; } |

11.3 More constructors

Like other methods, constructors can be overloaded, which means you can provide multiple constructors with different parameters. Java knows which constructor to invoke by matching the arguments you provide with the parameters of the constructors.

It is common to provide a constructor that takes no arguments, like the previous one, and a “value constructor”, like this one:

| public Time(int hour, int minute, double second) { this.hour = hour; this.minute = minute; this.second = second; } |

All this constructor does is copy values from the parameters to the instance variables.

In this example, the names and types of the parameters are the same as the instance variables.

As a result, the parameters shadow (or hide) the instance variables, so the keyword this is necessary to tell them apart.

Parameters don’t have to use the same names, but that’s a common style.

To invoke this second constructor, you have to provide arguments after the new operator.

This example creates a Time object that represents a fraction of a second before noon:

| Time time = new Time(11, 59, 59.9); |

Overloading constructors provides the flexibility to create an object first and then fill in the attributes, or collect all the information before creating the object itself.

Once you get the hang of it, writing constructors gets boring. You can write them quickly just by looking at the list of instance variables. In fact, some IDEs can generate them for you.

Pulling it all together, here is the complete class definition so far:

| public class Time { private int hour; private int minute; private double second; public Time() { this.hour = 0; this.minute = 0; this.second = 0.0; } public Time(int hour, int minute, double second) { this.hour = hour; this.minute = minute; this.second = second; } } |

11.4 Getters and setters

Recall that the instance variables of Time are private.

We can access them from within the Time class, but if we try to access them from another class, the compiler generates an error.

For example, here’s a new class called TimeClient, because a class that uses objects defined in another class is called a client:

| public class TimeClient { public static void main(String[] args) { Time time = new Time(11, 59, 59.9); System.out.println(time.hour); // compiler error } } |

If you try to compile this code, you will get a message like hour has private access in Time. There are three ways to solve this problem:

- We could make the instance variables

public. - We could provide methods to access the instance variables.

- We could decide that it’s not a problem, and refuse to let other classes access the instance variables.

The first choice is appealing because it’s simple. But the problem is that when Class A accesses the instance variables of Class B directly, A becomes “dependent” on B. If anything in B changes later, it is likely that A will have to change, too.

But if A only uses methods to interact with B, A and B are “independent”, which means that we can make changes in B without affecting A (as long as we don’t change the method signatures).

So if we decide that TimeClient should be able to read the instance variables of Time, we can provide methods to do it:

| public int getHour() { return this.hour; } public int getMinute() { return this.minute; } public int getSecond() { return this.second; } |

Methods like these are formally called “accessors”, but more commonly referred to as getters.

By convention, the method that gets a variable named something is called getSomething.

If we decide that TimeClient should also be able to modify the instance variables of Time, we can provide methods to do that, too:

| public void setHour(int hour) { this.hour = hour; } public void setMinute(int minute) { this.minute = minute; } public void setSecond(int second) { this.second = second; } |

These methods are formally called “mutators”, but more commonly known as setters.

The naming convention is similar; the method that sets something is usually called setSomething.

Writing getters and setters can get boring, but many IDEs can generate them for you based on the instance variables.

11.5 Displaying objects

If you create a Time object and display it with println:

| public static void main(String[] args) { Time time = new Time(11, 59, 59.9); System.out.println(time); } |

The output will look something like:

| Time@80cc7c0 |

When Java displays the value of an object type, it displays the name of the type and the address of the object (in hexadecimal). This address can be useful for debugging, if you want to keep track of individual objects.

To display Time objects in a way that is more meaningful to users, you could write a method to display the hour, minute, and second.

Using printTime in Section 4.6 as a starting point, we could write:

| public static void printTime(Time t) { System.out.print(t.hour); System.out.print(":"); System.out.println(t.minute); System.out.print(":"); System.out.println(t.second); } |

The output of this method, given the time object from the previous section, would be 11:59:59.9.

We can use printf to write it more concisely:

| public static void printTime(Time t) { System.out.printf("%02d:%02d:%04.1f\n", t.hour, t.minute, t.second); } |

As a reminder, you need to use \%d with integers and \%f with floating-point numbers.

The 02 option means “total width 2, with leading zeros if necessary”, and the 04.1 option means “total width 4, one digit after the decimal point, leading zeros if necessary”.

11.6 The toString method

Every object type has a method called toString that returns a string representation of the object.

When you display an object using print or println, Java invokes the object’s toString method.

By default it simply displays the type of the object and its address, but you can override this behavior by providing your own toString method.

For example, here is a toString method for Time:

| public String toString() { return String.format("%02d:%02d:%04.1f\n", this.hour, this.minute, this.second); } |

The definition does not have the keyword static, because it is not a static method.

It is an instance method, so called because when you invoke it, you invoke it on an instance of the class (Time in this case).

Instance methods are sometimes called “non-static”; you might see this term in an error message.

The body of the method is similar to printTime in the previous section, with two changes:

- Inside the method, we use

thisto refer to the current instance; that is, the object the method is invoked on. - Instead of

printf, it usesString.format, which returns a formattedStringrather than displaying it.

Now you can call toString directly:

| Time time = new Time(11, 59, 59.9); String s = time.toString(); |

Or you can invoke it indirectly through println:

| System.out.println(time); |

In this example, this in toString refers to the same object as time.

The output is 11:59:59.9.

11.7 The equals method

We have seen two ways to check whether values are equal: the == operator and the equals method.

With objects you can use either one, but they are not the same.

- The

==operator checks whether objects are identical; that is, whether they are the same object. - The

equalsmethod checks whether they are equivalent; that is, whether they have the same value.

The definition of identity is always the same, so the == operator always does the same thing.

But the definition of equivalence is different for different objects, so objects can define their own equals methods.

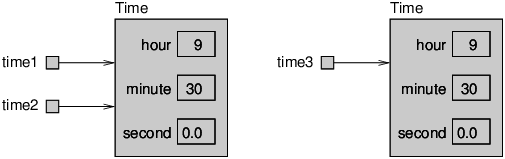

Consider the following variables:

| Time time1 = new Time(9, 30, 0.0); Time time2 = time1; Time time3 = new Time(9, 30, 0.0); |

Figure 11.2 is a state diagram that shows these variables and their values.

The assignment operator copies references, so time1 and time2 refer to the same object.

Because they are identical, time1 == time2 is true.

But time1 and time3 refer to different objects.

Because they are not identical, time1 == time3 is false.

By default, the equals method does the same thing as ==.

For Time objects, that’s probably not what we want.

For example, time1 and time3 represent the same time of day, so we should consider them equivalent.

We can provide an equals method that implements this notion of equivalence:

| public boolean equals(Time that) { return this.hour == that.hour && this.minute == that.minute && this.second == that.second; } |

equals is an instance method, so it uses this to refer to the current object and it doesn’t have the keyword static.

We can invoke equals as follows:

| time1.equals(time3); |

Inside the equals method, this refers to the same object as time1, and that refers to the same object as time3.

Since their instance variables are equal, the result is true.

Many objects use a similar notion of equivalence; that is, two objects are equivalent if their instance variables are equal. But other definitions are possible.

11.8 Adding times

Suppose you are going to a movie that starts at 18:50 (or 6:50 PM), and the running time is 2 hours 16 minutes. What time does the movie end?

We’ll use Time objects to figure it out.

Here are two ways we could “add” Time objects:

- We could write a static method that takes the two

Timeobjects as parameters. - We could write an instance method that gets invoked on one object and takes the other as a parameter.

To demonstrate the difference, we’ll do both. Here is a rough draft that uses the static approach:

| public static Time add(Time t1, Time t2) { Time sum = new Time(); sum.hour = t1.hour + t2.hour; sum.minute = t1.minute + t2.minute; sum.second = t1.second + t2.second; return sum; } |

And here’s how we would invoke the static method:

| Time startTime = new Time(18, 50, 0.0); Time runningTime = new Time(2, 16, 0.0); Time endTime = Time.add(startTime, runningTime); |

On the other hand, here’s what it looks like as an instance method:

| public Time add(Time t2) { Time sum = new Time(); sum.hour = this.hour + t2.hour; sum.minute = this.minute + t2.minute; sum.second = this.second + t2.second; return sum; } |

The changes are:

-

We removed the keyword

static. - We removed the first parameter.

- We replaced

t1withthis.

Optionally, you could replace t2 with that.

Unlike this, that is not a keyword; it’s just a slightly clever variable name.

And here’s how we would invoke the instance method:

| Time endTime = startTime.add(runningTime); |

That’s all there is to it. Static methods and instance methods do the same thing, and you can convert from one to the other with just a few changes.

There’s only one problem: the addition code itself is not correct.

For this example, it returns 20:66, which is not a valid time.

If second exceeds 59, we have to “carry” into the minutes column, and if minute exceeds 59, we have to carry into hour.

Here is a better version of add:

| public Time add(Time t2) { Time sum = new Time(); sum.hour = this.hour + t2.hour; sum.minute = this.minute + t2.minute; sum.second = this.second + t2.second; if (sum.second >= 60.0) { sum.second -= 60.0; sum.minute += 1; } if (sum.minute >= 60) { sum.minute -= 60; sum.hour += 1; } return sum; } |

It’s still possible that hour may exceed 23, but there’s no days attribute to carry into.

In that case, sum.hour -= 24 would yield the correct result.

11.9 Pure methods and modifiers

This implementation of add does not modify either of the parameters.

Instead, it creates and returns a new Time object.

As an alternative, we could have written a method like this:

| public void increment(double seconds) { this.second += seconds; while (this.second >= 60.0) { this.second -= 60.0; this.minute += 1; } while (this.minute >= 60) { this.minute -= 60; this.hour += 1; } } |

The increment method modifies an existing Time object.

It doesn’t create a new one, and it doesn’t return anything.

In contrast, methods like add are called pure because:

- They don’t modify the parameters.

- They don’t have any other “side effects”, like printing.

- The return value only depends on the parameters, not on any other state.

Methods like increment, which breaks the first rule, are sometimes called modifiers.

They are usually void methods, but sometimes they return a reference to the object they modify.

Modifiers can be more efficient because they don’t create new objects. But they can also be error-prone. When objects are aliased, the effects of modifiers can be confusing.

To make a class immutable, like String, you can provide getters but no setters and pure methods but no modifiers.

Immutable objects can be more difficult to work with, at first, but they can save you from long hours of debugging.

11.10 Vocabulary

- class:

- Previously, we defined a class as a collection of related methods. Now you know that a class is also a template for a new type of object.

- instance:

- A member of a class. Every object is an instance of some class.

- instantiate:

- Create a new instance of a class in the computer’s memory.

- data encapsulation:

- A technique for bundling multiple named variables into a single object.

- instance variable:

- An attribute of an object; a non-static variable defined at the class level.

- information hiding:

-

The practice of making instance variables

privateto limit dependencies between classes. - constructor:

- A special method that initializes the instance variables of a newly-constructed object.

- shadowing:

- Defining a local variable or parameter with the same name and type as an instance variable.

- client:

- A class that uses objects defined in another class.

- getter:

- A method that returns the value of an instance variable.

- setter:

- A method that assigns a value to an instance variable.

- override:

-

Replacing a default implementation of a method, such as

toString. - instance method:

-

A non-static method that has access to

thisand the instance variables. - identical:

- Two values that are the same; in the case of objects, two variables that refer to the same object.

- equivalent:

-

Two objects that are “equal” but not necessarily identical, as defined by the

equalsmethod. - pure method:

- A static method that depends only on its parameters and no other data.

- modifier method:

- A method that changes the state (instance variables) of an object.

11.11 Exercises

The code for this chapter is in the ch11 directory of ThinkJavaCode. See page ?? for instructions on how to download the repository. Before you start the exercises, we recommend that you compile and run the examples.

At this point you know enough to read Appendix B, which is about simple 2D graphics and animations. During the next few chapters, you should take a detour to read this appendix and work through the exercises.

Review the documentation of java.awt.Rectangle.

Which methods are pure?

Which are modifiers?

If you review the documentation of java.lang.String, you should see that there are no modifiers, because strings are immutable.

The implementation of increment in this chapter is not very efficient.

Can you rewrite it so it doesn’t use any loops?

Hint: Remember the modulus operator.

In the board game Scrabble, each tile contains a letter, which is used to spell words in rows and columns, and a score, which is used to determine the value of words.

- Write a definition for a class named

Tilethat represents Scrabble tiles. The instance variables should include a character namedletterand an integer namedvalue. - Write a constructor that takes parameters named

letterandvalueand initializes the instance variables. - Write a method named

printTilethat takes aTileobject as a parameter and displays the instance variables in a reader-friendly format. - Write a method named

testTilethat creates aTileobject with the letterZand the value10, and then usesprintTileto display the state of the object. - Implement the

toStringandequalsmethods for aTile. - Create getters and setters for each of the attributes.

The point of this exercise is to practice the mechanical part of creating a new class definition and code that tests it.

Date, an object type that contains three integers: year, month, and day.

This class should provide two constructors.

The first should take no parameters and initialize a default date.

The second should take parameters named year, month and day, and use them to initialize the instance variables.Write a main method that creates a new Date object named birthday.

The new object should contain your birth date.

You can use either constructor.

A rational number is a number that can be represented as the ratio of two integers. For example, 2/3 is a rational number, and you can think of 7 as a rational number with an implicit 1 in the denominator.

- Define a class called

Rational. ARationalobject should have two integer instance variables that store the numerator and denominator. - Write a constructor that takes no arguments and that sets the numerator to 0 and denominator to 1.

- Write an instance method called

printRationalthat displays aRationalin some reasonable format. - Write a

mainmethod that creates a new object with typeRational, sets its instance variables to some values, and displays the object. - At this stage, you have a minimal testable program. Test it and, if necessary, debug it.

- Write a

toStringmethod forRationaland test it usingprintln. - Write a second constructor that takes two arguments and uses them to initialize the instance variables.

- Write an instance method called

negatethat reverses the sign of a rational number. This method should be a modifier, so it should be void. Add lines tomainto test the new method. - Write an instance method called

invertthat inverts the number by swapping the numerator and denominator. It should be a modifier. Add lines tomainto test the new method. - Write an instance method called

toDoublethat converts the rational number to adouble(floating-point number) and returns the result. This method is a pure method; it does not modify the object. As always, test the new method. - Write an instance method named

reducethat reduces a rational number to its lowest terms by finding the greatest common divisor (GCD) of the numerator and denominator and dividing through. This method should be a pure method; it should not modify the instance variables of the object on which it is invoked.Hint: Finding the GCD only takes a few lines of code. Search the web for “Euclidean algorithm”.

- Write an instance method called

addthat takes aRationalnumber as an argument, adds it tothis, and returns a newRationalobject.There are several ways to add fractions. You can use any one you want, but you should make sure that the result of the operation is reduced so that the numerator and denominator have no common divisor (other than 1).

The purpose of this exercise is to write a class definition that includes a variety of methods, including constructors, static methods, instance methods, modifiers, and pure methods.

Are you using one of our books in a class?

We'd like to know about it. Please consider filling out this short survey.